Gareth O'Callaghan: Nothing has changed politically in 50 years

On a summer’s day in June 1977, Jack Lynch wiped the eyes of five political parties and other independents contesting the general election by winning an unprecedented landslide victory for Fianna Fáil.

“It’s like the days of Jack Lynch all over again,” the man sitting next to me on my bus journey into Cork told me dreamily during the week. I smiled and nodded. I didn’t have the heart to disagree with him.

Let’s remind ourselves then of those so-called halcyon days of the 1970s when politics possibly seemed to have a stronger, if somewhat mythical whiff of transparency about it than what’s been landed in our laps in recent times.

On a summer’s day in June 1977, Jack Lynch wiped the eyes of five political parties and other independents contesting the general election with an unprecedented landslide victory for Fianna Fáil.

Lynch with his trademark fedora and pipe, calm manner and widespread appeal zigzagged the country in his campaign bus to the roars of “Bring Back Jack” — a snappy slogan devised by the party’s director of elections Seamus Brennan.

‘Put Jack Back’ was the sticker that adorned tens of thousands of car bumpers all over the country, not to mention Jack Lynch hats and T-shirts, while the catchy campaign song ‘ ’ sung by Colm Wilkinson, for which he would later tell Bertie Ahern he never got paid a cent, was played from speaker horns attached to the car roofs belonging to campaigners.

Scroll for results in your area

RTÉ refused to air the song, while CIE bus drivers were banned from playing it due to the company’s neutral political stance. Truth was it had more to do with its cringeworthy awfulness than its political exultation. It’s still played at the start of every Fianna Fáil ard fheis.

Lynch’s powerful yet calm and amiable personality played a huge role in the overwhelming victory, the most significant electoral win in history up to that point, forcing the resignation of his two opposition players, Liam Cosgrave and Brendan Corish, whose Fine Gael/Labour coalition had bombed at the polls.

Nostalgia has a way of making us forget what we’d prefer not to recall while retaining those more sentimental moments within the frame width of our rose-tinted glasses.

Clever choreography on election campaign trails had a knack of blurring the incredulous promises that would never see the light of day, as they still do; and Jack Lynch’s promises were no different.

His party’s manifesto promised to abolish road tax and rates on private dwellings. He even promised a greater say for women, along with other personal enticements that read like a storyline out of a Mills & Boon novel.

Economist and former governor of the Central Bank, TK Whitaker wrote that the manifesto “could not be described as an economic programme but rather as a national disaster". And that became its reality.

It would end up suffocating the economy in foreign debt while paving the way for the damning recession of the 1980s — a list of pledges filled with “irrational optimism”, as Whitaker described it.

By 1977, our national debt had taken 50 years to reach £1bn. Over the four years that followed it rose to £10bn. Lynch resigned in 1979, although many say he was forced out by one of his own, namely Charles J Haughey.

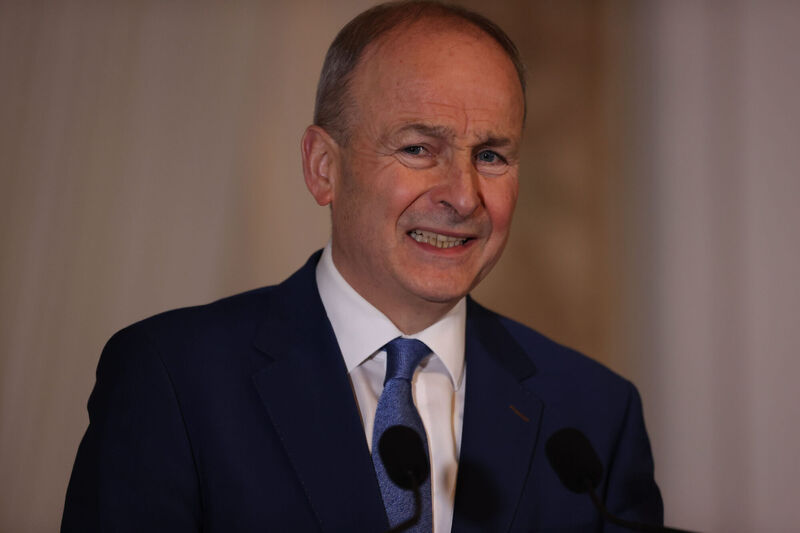

There are many similarities between Jack Lynch and Micheál Martin. Martin also has an endearing quality and a genuine interest in people, those close to him say. It would be wrong to think that such qualities are tools of the political trade; they’re not, and Martin finds himself in that small group who do not come across as disingenuous.

I believe the two men would have worked well together. However, almost 50 years later, it would be wrong to compare a 1970s politician with the man who is about to become Taoiseach.

But enough of the plámás If one fact has emerged from last week’s election, it’s that nothing has changed politically. If anything, it was a clever set-up; as though it were known that the new government wouldn’t be any different to its predecessor.

It achieved nothing, if only to prove that the ‘haves’ are happy with their status quo, while the ‘have nots’ — those who feel so defeated they’ve lost all faith in politics — didn't bother to vote. In the grand scheme, the landscape looks no different, while the cumulative cost of last weekend’s stunt runs to €10m.

When an election is called, it's perceived by voters that the incumbent government is asking for a mandate to continue governing; but if the country is in a state of crisis then no government will want to call an election, because if they do then they know they're out of a job.

If a large percentage of the electorate is enjoying a decent standard of living, then when an election is called, those voters will want to retain the status quo, rather than risk uncharted territory.

Few governments will wait for a crisis to go to the people; they'll only take that risk if they believe it will pay off. They know who's pulling the strings here and it's not us.

A general election is like a game of roulette. In order to determine the winning number, a croupier spins the wheel one way and then spins a ball in the opposite direction.

Imagine the croupier is the politician, the wheel is the election, and the ball is the voter. What if the croupier declares you the loser even though you’ve watched the ball land in your favour? What if the outcome of the game has already been planned before you even moved your chips into play?

It’s clear that the outcome of this election was already pre-determined for the two largest parties, the major players in the history of politics. This was always going to be a centre-right outcome. But are we now looking at a risk-stacked three- or even four-way coalition? When the rainbow coalition left office in 1997, unemployment stood at 10.9%.

Fine Gael is now insisting on “parity of esteem” with Fianna Fáil as a basic condition in any coalition agreement. This new government, once formed, won’t reflect how many people voted or for whom.

History has shown that minority parties — look at the Greens’ performance last week — suffer badly in any coalition. The reason a voter is drawn to a party is because of what it’s offering, and how its policies are reflected in the voter’s needs and grievances.

Making concessions is unavoidable when a small party hitches itself to a bigger player, but voters don’t want concessions — it’s the reason they voted for you, and you sold out.

But as we’ve seen, you don’t need to be small to sell out. Jack Lynch sold out during his time as taoiseach, and no doubt so will Micheál Martin, yet again, as would the leader of any party who is given a chance to govern.

In roulette, the wheel and the ball will always spin in opposite directions — much like politics. When you vote, you take a gamble; because what you finally get might not be what you hoped for.